*** This tour was published in March 2021, when the Covid-19 pandemic was active. Please wear a mask/face covering and maintain a social distance of 6 ft from people not in your household. Visit www.emergencyslo.org for the latest in public health advice. ***

A Self-guided Walking Tour of Mission Plaza in 1858 and the Committee of Vigilance

Site 4: Walter Murray Adobe

In 1859, a deed was recorded transferring title of this property to Walter Murray, the leader of the Committee of Vigilance. The land was sold to Murray by John Wilson, husband to Ramona Wilson and stepfather to Romualdo Pacheco, Jr.

Walter Murray was not only the leader of the Vigilantes, he would also provide details of Committee activities that were published most notably in the earliest history of San Luis Obispo County by Myron Angel (1883).

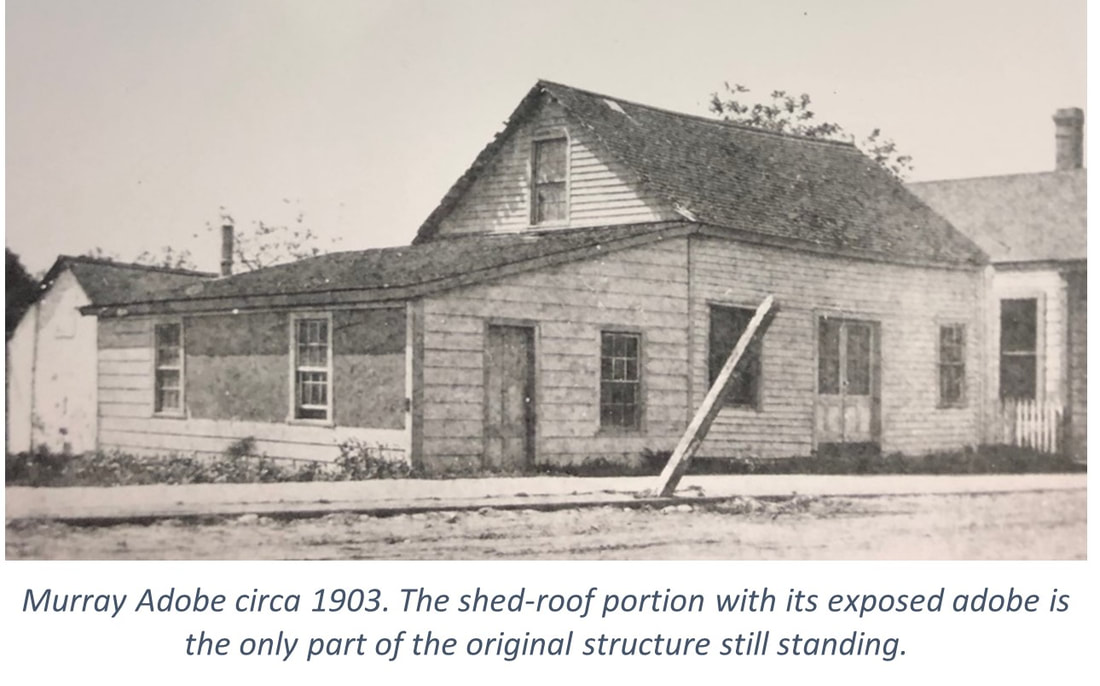

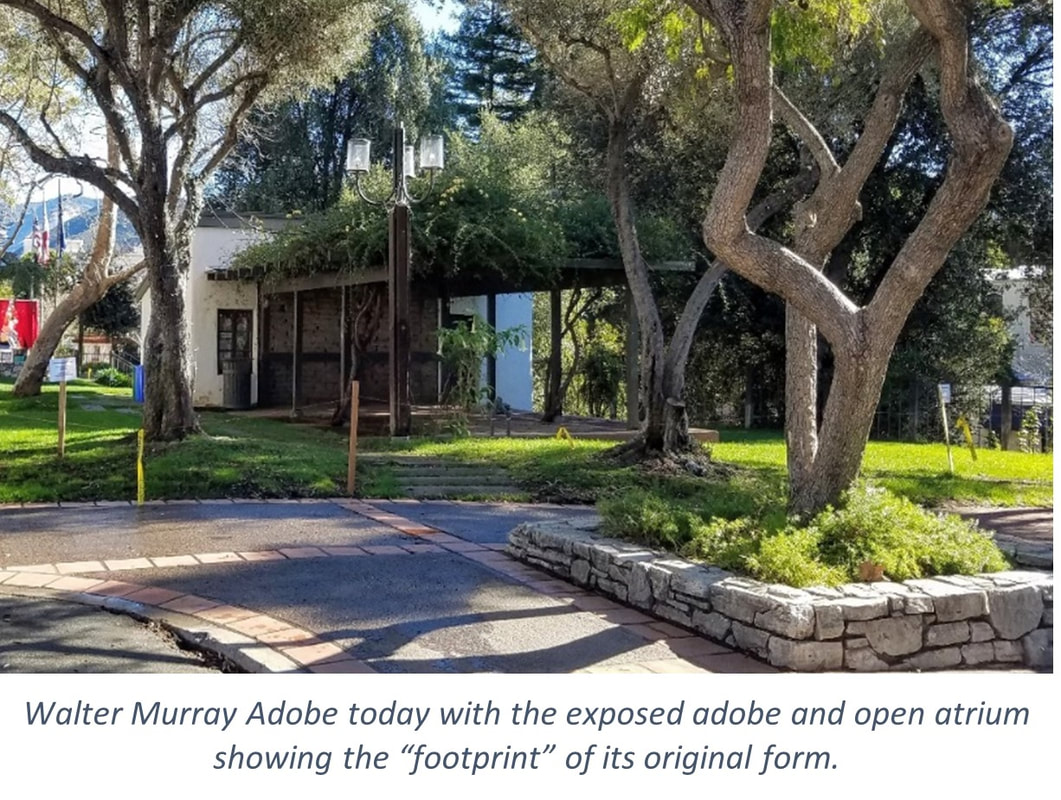

It is not known definitively that this adobe (clad in boards here) existed in 1858, or whether Murray had it built later. When constructed, Murray advertised it as his law offices. The adobe structure was also the original office of the San Luis Obispo Tribune, founded by Walter Murray in 1869, still published as the County’s “newspaper of record.”

May 20, 1858 was a dramatic day in the story of the Vigilantes, eight days after the triple murder in North County, and a week after the angry mob had lynched Santos Peralta in the jail at Site 3. Sheriff Francisco Castro and a 15-man posse had been scouring the countryside for the bandidos, but they had returned with no prisoners except for the luckless “Joaquin” who would be hanged later that day, in spite of having no connection to the triple murder nor the Powers-Linares gang.

In 1859, a deed was recorded transferring title of this property to Walter Murray, the leader of the Committee of Vigilance. The land was sold to Murray by John Wilson, husband to Ramona Wilson and stepfather to Romualdo Pacheco, Jr.

Walter Murray was not only the leader of the Vigilantes, he would also provide details of Committee activities that were published most notably in the earliest history of San Luis Obispo County by Myron Angel (1883).

It is not known definitively that this adobe (clad in boards here) existed in 1858, or whether Murray had it built later. When constructed, Murray advertised it as his law offices. The adobe structure was also the original office of the San Luis Obispo Tribune, founded by Walter Murray in 1869, still published as the County’s “newspaper of record.”

May 20, 1858 was a dramatic day in the story of the Vigilantes, eight days after the triple murder in North County, and a week after the angry mob had lynched Santos Peralta in the jail at Site 3. Sheriff Francisco Castro and a 15-man posse had been scouring the countryside for the bandidos, but they had returned with no prisoners except for the luckless “Joaquin” who would be hanged later that day, in spite of having no connection to the triple murder nor the Powers-Linares gang.

|

It began very early – 3 a.m., according to Walter Murray. Sheriff Castro, with the assistance of Murray and his posse, tried to arrest Pio Linares, the alleged leader of the gang that murdered Baratie and Borel—though nobody had yet placed Linares at the scene of the crime.

At that time, Linares was at home with his wife in their adobe that still stands on Andrews Street off present-day San Luis Drive. When confronted by the lawmen, Linares refused to leave his home, whereupon the posse set fire to the roof. Linares escaped amidst a hail of bullets, leaving his wife and the smoldering home, and managed to get away to the Los Osos Valley. Linares holed up there, not far from the adobe where he had been raised on his late father’s land grant. Now fugitives from the vigilante justice that awaited them, Linares and a few of his gang members managed to elude the Vigilantes for three weeks. |

Later that morning, as soon as Walter Murray learned that the posse had failed to take Pio Linares, he met with the posse at his home on upper Monterey Street located within a few hundred feet of the still-smoking Linares home. Murray organized them into a “Committee of Vigilance,” a popular form of frontier justice that had already been employed in San Francisco and Los Angeles to suppress the alleged criminal behavior of various “non-American” bandidos (i.e., Chinese, Chileans, Californios, etc.).

Murray headed the Executive Committee and I.H. Hill was designated as the “Sheriff,” displacing elected Sheriff Francisco Castro. The Committee dispatched a posse of three to San Francisco to locate and arrest Jack Powers. He had been warned by an associate and escaped the dragnet. Powers sent word that he would return voluntarily to San Luis Obispo to face his accusers. The Vigilantes awaited his expected arrival on the steamship Senator at Avila Bay on June 4. They were eager to hoist him on the same rope where "Joaquin" had strangled to death—but Powers had absconded to Mexico on another boat.

Meanwhile, on June 3, Luciano Tapia returned to the county after “escorting” Andrea Baratie, the surviving widow of the Baratie/Borel murder, from San Juan Bautista. After a short search, a posse promptly arrested Tapia and hauled him before Murray’s Committee of Vigilance for interrogation.

Tapia was the only member of the gang who gave a complete description of the murders, pointing the finger at others and denying that he had kidnapped Mrs. Baratie—to the contrary, he insisted that he had rescued her. He certainly expected mercy for having persuaded Froilan Servin to ignore the gang’s “Dead Men Tell No Tales” dictum and spare the lives of the two servants and Andrea Baratie. Servin had fled, but he would be arrested much later—the only one of the Gang to be provided a de jure trial and sentenced properly (see below).

No mercy was shown to Tapia: The Committee extracted a lengthy statement from their prisoner, ten men signed his death sentence, and Tapia was hanged the very same day, June 3 at Site 2.

On June 8, the Vigilantes made another “arrest” – this one of Jose Antonia Garcia. The arresting officer was “Sheriff” D.D. Blackburn, another sheriff appointed by the Vigilantes. Blackburn caught up with Garcia in Santa Barbara and transported him back to SLO where he gave testimony that tied him to the earlier murder of two cattle drovers in November 1857. Garcia denied taking part in the actual murders—he’d been watering his horses and was horrified at the crime—but his protestation of innocence did not help. The Vigilantes allowed him to write a letter to his mother, and then he too was led to the gallows at Site 2.

On June 10, the Vigilantes learned that Pio Linares had been spotted hiding out in the dense woodland near his original homestead in Los Osos. A posse of armed Vigilantes on horseback found him and two comrades, all well-armed and well-hidden in the brush. A two-day shootout ensued, resulted in the death of one Vigilante (John Matlock), the wounding of two others (including Walter Murray), and a fatal shot to the head of Pio Linares.

The other two alleged bandidos, Miguel Blanco and Desiderio Grijalva, were apprehended alive. The Committee brought them to the jail, forced a confession from them, and held a public trial at the Mission courtroom the next day. The hanging was delayed until Monday, June 14, as Sunday was the day of John Matlock’s funeral, attended by most in the town.

With the execution of Blanco and Grijalva, by now six Californios had been hanged—and of those six, only these two fellows actually confessed to the triple murder. Did Pio Linares bear some share of their guilt? A bullet had already made that question moot.

Murray headed the Executive Committee and I.H. Hill was designated as the “Sheriff,” displacing elected Sheriff Francisco Castro. The Committee dispatched a posse of three to San Francisco to locate and arrest Jack Powers. He had been warned by an associate and escaped the dragnet. Powers sent word that he would return voluntarily to San Luis Obispo to face his accusers. The Vigilantes awaited his expected arrival on the steamship Senator at Avila Bay on June 4. They were eager to hoist him on the same rope where "Joaquin" had strangled to death—but Powers had absconded to Mexico on another boat.

Meanwhile, on June 3, Luciano Tapia returned to the county after “escorting” Andrea Baratie, the surviving widow of the Baratie/Borel murder, from San Juan Bautista. After a short search, a posse promptly arrested Tapia and hauled him before Murray’s Committee of Vigilance for interrogation.

Tapia was the only member of the gang who gave a complete description of the murders, pointing the finger at others and denying that he had kidnapped Mrs. Baratie—to the contrary, he insisted that he had rescued her. He certainly expected mercy for having persuaded Froilan Servin to ignore the gang’s “Dead Men Tell No Tales” dictum and spare the lives of the two servants and Andrea Baratie. Servin had fled, but he would be arrested much later—the only one of the Gang to be provided a de jure trial and sentenced properly (see below).

No mercy was shown to Tapia: The Committee extracted a lengthy statement from their prisoner, ten men signed his death sentence, and Tapia was hanged the very same day, June 3 at Site 2.

On June 8, the Vigilantes made another “arrest” – this one of Jose Antonia Garcia. The arresting officer was “Sheriff” D.D. Blackburn, another sheriff appointed by the Vigilantes. Blackburn caught up with Garcia in Santa Barbara and transported him back to SLO where he gave testimony that tied him to the earlier murder of two cattle drovers in November 1857. Garcia denied taking part in the actual murders—he’d been watering his horses and was horrified at the crime—but his protestation of innocence did not help. The Vigilantes allowed him to write a letter to his mother, and then he too was led to the gallows at Site 2.

On June 10, the Vigilantes learned that Pio Linares had been spotted hiding out in the dense woodland near his original homestead in Los Osos. A posse of armed Vigilantes on horseback found him and two comrades, all well-armed and well-hidden in the brush. A two-day shootout ensued, resulted in the death of one Vigilante (John Matlock), the wounding of two others (including Walter Murray), and a fatal shot to the head of Pio Linares.

The other two alleged bandidos, Miguel Blanco and Desiderio Grijalva, were apprehended alive. The Committee brought them to the jail, forced a confession from them, and held a public trial at the Mission courtroom the next day. The hanging was delayed until Monday, June 14, as Sunday was the day of John Matlock’s funeral, attended by most in the town.

With the execution of Blanco and Grijalva, by now six Californios had been hanged—and of those six, only these two fellows actually confessed to the triple murder. Did Pio Linares bear some share of their guilt? A bullet had already made that question moot.

|

Having killed Linares and put two of the gang on the gallows, the Committee of Vigilance now gained significant new membership. At its peak, the Committee’s roster included almost 100 names—and a third were Hispanic.

The Committee assigned to Californio Romualdo Pacheco the dangerous task of pursuing Rafael Herrada (“El Huero”), thought to be in Los Angeles. Blanco and Grijalva had identified El Huero as one of the murderers. El Huero had been hiding out with Pio Linares, Miguel Blanco, and Desiderio Grijalva, but he managed to avoid capture during the extended shootout in the Los Osos Valley. |

Pacheco was already a State Senator at the age of 26, and destined for much bigger things. He and his posse were hot on the trail of El Huero for weeks, but never caught him. They DID, however, catch up with Nieves Robles in Santa Barbara. Pacheco transported Robles back to San Luis Obispo and handed him over to Sheriff Castro. As with the others however, the Vigilantes forced Castro to give up Robles to them.

There’s no record of a statement by Robles, nor any written charges by the Committee of Vigilance. It was simply understood that he had associated with Linares, and was named by one or more witnesses. Robles was hanged on June 28—the last of the seven Californios to be lynched in this spate of retribution set in motion by the triple murder in North County.

One more member of the Powers Linares Gang would be captured in September: Froilan Servin, who had participated in the murders of Borel and Baratie. He’d been persuaded by the late Luciano Tapia to spare the lives of the two servants. Servin actually got a trial, and in November he was convicted and sentenced to seventeen years of hard labor at San Quentin. His defense attorney in that trial? Walter Murray. (Servin died soon after in the harsh conditions at San Quentin).

The Committee of Vigilance disbanded after the hanging of Nieves Robles, the seventh Californio presumed to be associated with the Powers-Linares Gang, or with Joaquin Murietta. In the 160+ years since these events, our criminal justice system has tried to assure due process for criminal defendants in compliance with the Constitution. This system can always be improved, especially to assure that people of color are treated equitably. Nonetheless, we have moved beyond the dark days of 1858.

The Tour of 1858 Mission Plaza now moves to the front of the Mission at Site #5. We return to the story of Ramona Pacheco and her role in bringing peace, mercy, and justice to California in 1846, as the state was shifting from the tenuous jurisdiction of the Californios to its destiny in union with the United States of America.

There’s no record of a statement by Robles, nor any written charges by the Committee of Vigilance. It was simply understood that he had associated with Linares, and was named by one or more witnesses. Robles was hanged on June 28—the last of the seven Californios to be lynched in this spate of retribution set in motion by the triple murder in North County.

One more member of the Powers Linares Gang would be captured in September: Froilan Servin, who had participated in the murders of Borel and Baratie. He’d been persuaded by the late Luciano Tapia to spare the lives of the two servants. Servin actually got a trial, and in November he was convicted and sentenced to seventeen years of hard labor at San Quentin. His defense attorney in that trial? Walter Murray. (Servin died soon after in the harsh conditions at San Quentin).

The Committee of Vigilance disbanded after the hanging of Nieves Robles, the seventh Californio presumed to be associated with the Powers-Linares Gang, or with Joaquin Murietta. In the 160+ years since these events, our criminal justice system has tried to assure due process for criminal defendants in compliance with the Constitution. This system can always be improved, especially to assure that people of color are treated equitably. Nonetheless, we have moved beyond the dark days of 1858.

The Tour of 1858 Mission Plaza now moves to the front of the Mission at Site #5. We return to the story of Ramona Pacheco and her role in bringing peace, mercy, and justice to California in 1846, as the state was shifting from the tenuous jurisdiction of the Californios to its destiny in union with the United States of America.