A Self-guided Walking Tour of Mission Plaza in 1858 and the Committee of Vigilance

A Guide to the Main Characters

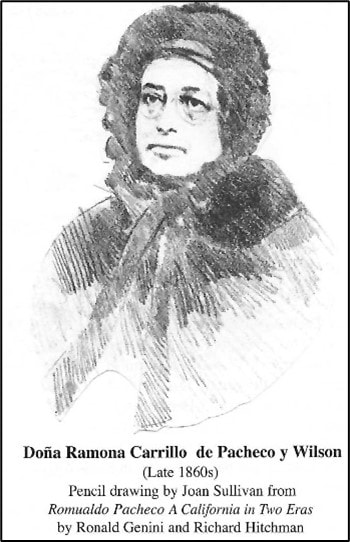

Ramona Carrillo de Pacheco y Wilson

Ramona Wilson was the daughter of a prominent Santa Barbara family, the Carrillos. In 1826, she had married Romualdo Pacheco, Sr. but only five years later, within three weeks after she gave birth to their second son Romualdo Jr., her husband was mortally wounded in the Battle of Cahuenga Pass.

In spite of this tragedy, Ramona would continue to rise in the rapidly evolving society of Alta California, marrying the dashing and wealthy Scottish shipping magnate John Wilson in 1836. Her son Romualdo, Jr. was elected a SLO County judge at 25, and lead a remarkable career in politics, becoming the first and (so far) ONLY Latino Governor of California in 1875.

Ramona Wilson preferred to reside in the home that John Wilson had built in 1845 next to the Mission (Site #1, now the History Center/Carnegie Library), rather than the “Wilson adobe” that still stands in the Los Osos Valley near Turri Road. A staunch Catholic, Ramona took advantage of the proximity of her “town home” to the Mission. According to local historian and artist Joan Sullivan: “Mrs. Wilson, an extremely religious person, attended Church three of four times a day and used the walk of flagstones connecting their home with the mission, wearing ‘deep hollows in the stone by her feet, passing into the chapel for prayer.’”

This is the same path that our Self-Guided Walking tour will take – and the same route that Ramona Wilson would use in December 1846 to plead with Colonel John C. Fremont to spare the life of her cousin Don Jose de Jesus Pico. That story reveals the immense positive influence Ramona Wilson gave to the emerging State of California. It’s told in more detail in Site #5.

Ramona Wilson was the daughter of a prominent Santa Barbara family, the Carrillos. In 1826, she had married Romualdo Pacheco, Sr. but only five years later, within three weeks after she gave birth to their second son Romualdo Jr., her husband was mortally wounded in the Battle of Cahuenga Pass.

In spite of this tragedy, Ramona would continue to rise in the rapidly evolving society of Alta California, marrying the dashing and wealthy Scottish shipping magnate John Wilson in 1836. Her son Romualdo, Jr. was elected a SLO County judge at 25, and lead a remarkable career in politics, becoming the first and (so far) ONLY Latino Governor of California in 1875.

Ramona Wilson preferred to reside in the home that John Wilson had built in 1845 next to the Mission (Site #1, now the History Center/Carnegie Library), rather than the “Wilson adobe” that still stands in the Los Osos Valley near Turri Road. A staunch Catholic, Ramona took advantage of the proximity of her “town home” to the Mission. According to local historian and artist Joan Sullivan: “Mrs. Wilson, an extremely religious person, attended Church three of four times a day and used the walk of flagstones connecting their home with the mission, wearing ‘deep hollows in the stone by her feet, passing into the chapel for prayer.’”

This is the same path that our Self-Guided Walking tour will take – and the same route that Ramona Wilson would use in December 1846 to plead with Colonel John C. Fremont to spare the life of her cousin Don Jose de Jesus Pico. That story reveals the immense positive influence Ramona Wilson gave to the emerging State of California. It’s told in more detail in Site #5.

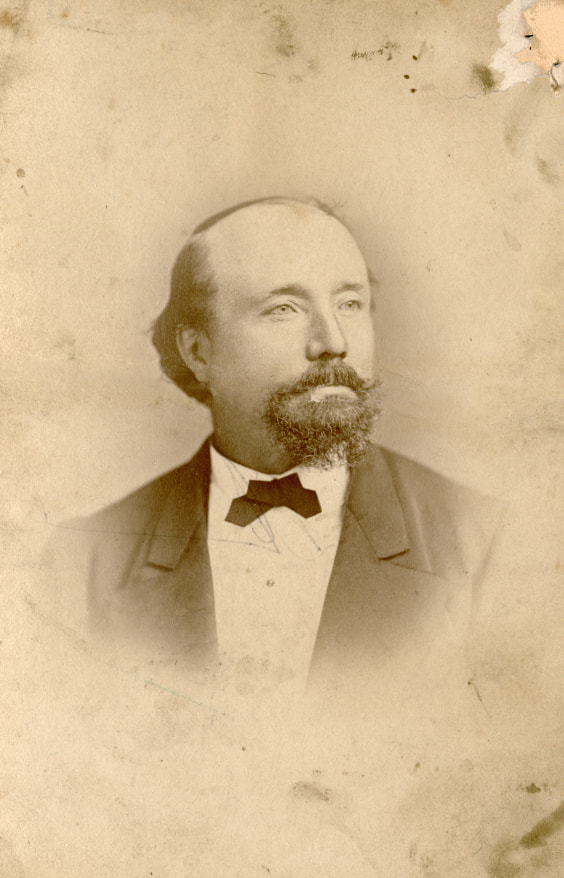

Walter Murray

Walter Murray arrived in California in 1847, during a short stint in a regiment of New York Volunteers in the War with Mexico. After mustering out, Walter Murray struck out to the gold fields in the Sierra to try his luck at mining. He had none, but like so many other unlucky miners he found more success in the business of publishing the Sonora Herald for a short time. In Sonora, he also met Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. and was convinced to follow him to Pacheco’s hometown of San Luis Obispo. By then, he had married a Chilean woman, Mercedes Espinosa, and started a family, and established himself as a lawyer – in fact, one of his first cases was to defend an alleged member of the Powers-Linares “Gang,” Nieves Robles: Murray succeeded in getting Robles acquitted of the charge of murdering two Basque cattle drovers in November, 1857. By the Spring of 1858, however, Murray had turned against Powers and led the Vigilantes to stamp out the “Powers-Linares” gang – culminating in hanging Nieves Robles in June 1858.

Murray resumed his law practice, acquiring the “Murray Adobe” (Site #4) and using it as his law office. In the 1858 election, having earned his reputation as a leader of the Committee of Vigilance, he was elected to the State Assembly. After the Civil War, he ran for various offices with mixed results before being appointed to the bench in 1873. Only two years later, Murray died before his 49th birthday, leaving Mercedes with six children.

Walter Murray arrived in California in 1847, during a short stint in a regiment of New York Volunteers in the War with Mexico. After mustering out, Walter Murray struck out to the gold fields in the Sierra to try his luck at mining. He had none, but like so many other unlucky miners he found more success in the business of publishing the Sonora Herald for a short time. In Sonora, he also met Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. and was convinced to follow him to Pacheco’s hometown of San Luis Obispo. By then, he had married a Chilean woman, Mercedes Espinosa, and started a family, and established himself as a lawyer – in fact, one of his first cases was to defend an alleged member of the Powers-Linares “Gang,” Nieves Robles: Murray succeeded in getting Robles acquitted of the charge of murdering two Basque cattle drovers in November, 1857. By the Spring of 1858, however, Murray had turned against Powers and led the Vigilantes to stamp out the “Powers-Linares” gang – culminating in hanging Nieves Robles in June 1858.

Murray resumed his law practice, acquiring the “Murray Adobe” (Site #4) and using it as his law office. In the 1858 election, having earned his reputation as a leader of the Committee of Vigilance, he was elected to the State Assembly. After the Civil War, he ran for various offices with mixed results before being appointed to the bench in 1873. Only two years later, Murray died before his 49th birthday, leaving Mercedes with six children.

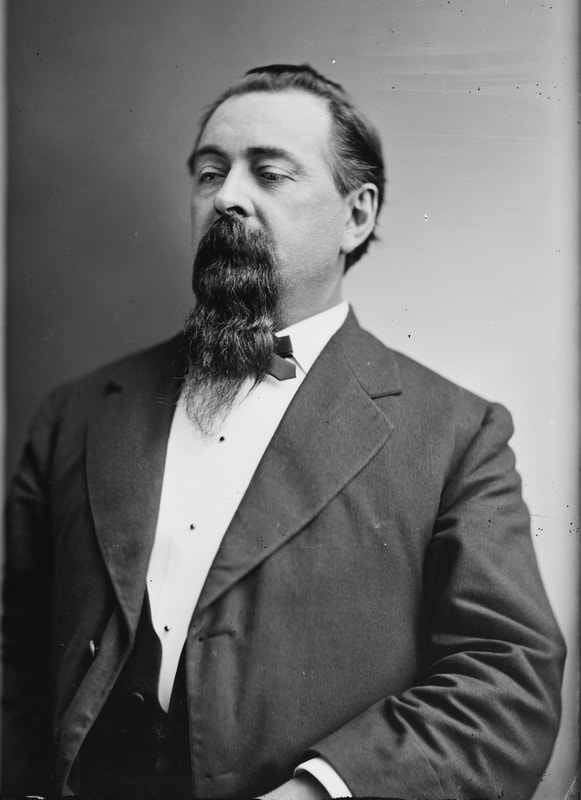

Romualdo Pacheco, Jr.

Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. was the second son of the senior Romualdo and Ramona Carrillo de Pacheco. After his father’s death, Ramona married John Wilson, the wealthy Scottish sea captain in Santa Barbara in 1836. Wilson later moved the family to San Luis Obispo County (Site #1), and sent Romualdo and his brother to Hawaii to receive a “proper” (Protestant) education. By the time he returned in 1846, Alta California was at war. Romualdo swore allegiance to the U.S. In 1853, in one of the first elections in San Luis Obispo County, voters elected him to be a judge at the age of 22, and four years hence, as State Senator representing SLO County. He did not sign on as a member of the Committee of Vigilance in 1858, but he did lead the posse who tracked down Nieves Robles and returned him to face the gallows (Site #2) in late June of that year.

During the Civil War, Pacheco was commissioned as a Brigadier General, serving with Union forces in Southern California, while also serving as State Treasurer. In the middle of that service, he also married Mary McIntire, a 22-year old playwright; they would have 3 children together. Elected as Lieutenant Governor in 1871, he assumed office as the first and (so far) ONLY Hispanic Governor of California in 1875, when incumbent Governor Newton Booth ascended to the US Senate. Elected to the US Congress twice, he resided in Mexico for five years before President Benjamin Harrison chose him as Ambassador to various Central American countries.

Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. ultimately returned to the Bay Area in 1893 and died in 1899 at age 67. For almost all of his adult life, Romualdo Pacheco Jr. had served his adopted State and nation as an elected official and statesman of the highest order.

Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. was the second son of the senior Romualdo and Ramona Carrillo de Pacheco. After his father’s death, Ramona married John Wilson, the wealthy Scottish sea captain in Santa Barbara in 1836. Wilson later moved the family to San Luis Obispo County (Site #1), and sent Romualdo and his brother to Hawaii to receive a “proper” (Protestant) education. By the time he returned in 1846, Alta California was at war. Romualdo swore allegiance to the U.S. In 1853, in one of the first elections in San Luis Obispo County, voters elected him to be a judge at the age of 22, and four years hence, as State Senator representing SLO County. He did not sign on as a member of the Committee of Vigilance in 1858, but he did lead the posse who tracked down Nieves Robles and returned him to face the gallows (Site #2) in late June of that year.

During the Civil War, Pacheco was commissioned as a Brigadier General, serving with Union forces in Southern California, while also serving as State Treasurer. In the middle of that service, he also married Mary McIntire, a 22-year old playwright; they would have 3 children together. Elected as Lieutenant Governor in 1871, he assumed office as the first and (so far) ONLY Hispanic Governor of California in 1875, when incumbent Governor Newton Booth ascended to the US Senate. Elected to the US Congress twice, he resided in Mexico for five years before President Benjamin Harrison chose him as Ambassador to various Central American countries.

Romualdo Pacheco, Jr. ultimately returned to the Bay Area in 1893 and died in 1899 at age 67. For almost all of his adult life, Romualdo Pacheco Jr. had served his adopted State and nation as an elected official and statesman of the highest order.

Jack Powers

Jack Powers, in contrast, was the “bad boy” in town. As author Pete Kelley suggests, by 1858, Powers had “gone native:” He had made and lost a considerable fortune in the gold fields and gambling halls of Northern California, and he’d been exiled from Santa Barbara as a deadbeat with a very loose trigger finger. By 1857, when he decided to make San Luis Obispo his base of operations, he had warrants for his arrest in both Los Angeles and San Francisco. He was frequently seen in the company of Pio Linares and other disgruntled Californios in the gambling houses and billiards halls along Monterey, Chorro and Higuera Streets.

Based on popular descriptions of this larger-than-life character, Jack Powers is pictured here as he is described by his contemporaries – a gregarious Irish gambler, popular dancer, superb horseman, and man-about-town with friends in places both very high and very low. Women loved him. Powers did not swing from a rope at Site #2, but if they had caught him, the Vigilantes would have hanged him here in a New York minute.

Instead, after learning that the Vigilantes had dispatched a posse of three men to San Francisco to arrest him, Powers was able to elude his captors and go into hiding. He then deceived the Committee into thinking that he would return to SLO to face his accusers. Rather than disembarking at Avila Bay from the steamship that took him south from San Francisco, Powers took another ship and escaped the Vigilantes, fleeing to Mexico and abandoning California altogether. Jack Powers did not survive for long, however, dying in Arizona territory, October 1860 by the hand of unknown assailants, his corpse devoured by ravenous swine.

Jack Powers, in contrast, was the “bad boy” in town. As author Pete Kelley suggests, by 1858, Powers had “gone native:” He had made and lost a considerable fortune in the gold fields and gambling halls of Northern California, and he’d been exiled from Santa Barbara as a deadbeat with a very loose trigger finger. By 1857, when he decided to make San Luis Obispo his base of operations, he had warrants for his arrest in both Los Angeles and San Francisco. He was frequently seen in the company of Pio Linares and other disgruntled Californios in the gambling houses and billiards halls along Monterey, Chorro and Higuera Streets.

Based on popular descriptions of this larger-than-life character, Jack Powers is pictured here as he is described by his contemporaries – a gregarious Irish gambler, popular dancer, superb horseman, and man-about-town with friends in places both very high and very low. Women loved him. Powers did not swing from a rope at Site #2, but if they had caught him, the Vigilantes would have hanged him here in a New York minute.

Instead, after learning that the Vigilantes had dispatched a posse of three men to San Francisco to arrest him, Powers was able to elude his captors and go into hiding. He then deceived the Committee into thinking that he would return to SLO to face his accusers. Rather than disembarking at Avila Bay from the steamship that took him south from San Francisco, Powers took another ship and escaped the Vigilantes, fleeing to Mexico and abandoning California altogether. Jack Powers did not survive for long, however, dying in Arizona territory, October 1860 by the hand of unknown assailants, his corpse devoured by ravenous swine.

Pio Linares

Pio Linares was also a Californio, but fate dealt him a very different hand than Romualdo Pacheco. Linares was heir to Victor Linares, a prominent citizen of Alta California and among the largest recipients of Mexican land grants in Alta California. With the onset of American rule, however, the Linares family would lose their land in the new political economy that largely displaced the Californios. All Mexican citizens who resided in Alta California prior to 1847 were promised American citizenship – but in many cases, those Californios who held title to Mexican or Spanish land grants would lose their lands through a combination of extended legal processes, fraud, and outright squatting by hordes of American settlers.

In the case of the Linares’ land, their title was usurped even more quickly: Captain John Wilson (Site #1) acquired the Linares’ land grants in 1853 from Miguela Garcia de Linares, the widow of Victor Linares and mother of five, in a third-party transaction involving Augustine Albarelli. Author Pete Kelley implies that Wilson’s buyout of the Linares land grant deprived Pio Linares of a significant part of his inheritance. Did it provoke him to despise Wilson and all the Americans who had come to dominate the lands and wealth of the new State of California? We may never know – but we do know, based on the writings of Walter Murray, that Pio Linares would soon be seen by the Americans as an alleged (but never convicted) thief and murderer.

Pio Linares resided with his wife Maria Antonia in an adobe on Andrews Street in San Luis Obispo – a structure that still stands, though May 20, 1858, its roof was set afire by a posse under direction of Sheriff Castro in order to smoke out this Californio. He escaped in a hail of bullets and managed to survive two more weeks, until cornered in the dense brush not far from the home where he had been brought up, a structure now known as the “Wilson Adobe” near Turri Lane in Los Osos. After a furious, two-day shootout where he and his two companions were surrounded by the Vigilantes, Linares was shot in the head; Walter Murray later noted that he refused the last rites, surely the mark of a “devilish man.” His two fellow fugitives, Desiderio Gonsalves and Miguel Blanco, were captured alive, thrown into jail (Site #3), put on “trial” by the Vigilantes, and hanged (Site #2).

Pio Linares was also a Californio, but fate dealt him a very different hand than Romualdo Pacheco. Linares was heir to Victor Linares, a prominent citizen of Alta California and among the largest recipients of Mexican land grants in Alta California. With the onset of American rule, however, the Linares family would lose their land in the new political economy that largely displaced the Californios. All Mexican citizens who resided in Alta California prior to 1847 were promised American citizenship – but in many cases, those Californios who held title to Mexican or Spanish land grants would lose their lands through a combination of extended legal processes, fraud, and outright squatting by hordes of American settlers.

In the case of the Linares’ land, their title was usurped even more quickly: Captain John Wilson (Site #1) acquired the Linares’ land grants in 1853 from Miguela Garcia de Linares, the widow of Victor Linares and mother of five, in a third-party transaction involving Augustine Albarelli. Author Pete Kelley implies that Wilson’s buyout of the Linares land grant deprived Pio Linares of a significant part of his inheritance. Did it provoke him to despise Wilson and all the Americans who had come to dominate the lands and wealth of the new State of California? We may never know – but we do know, based on the writings of Walter Murray, that Pio Linares would soon be seen by the Americans as an alleged (but never convicted) thief and murderer.

Pio Linares resided with his wife Maria Antonia in an adobe on Andrews Street in San Luis Obispo – a structure that still stands, though May 20, 1858, its roof was set afire by a posse under direction of Sheriff Castro in order to smoke out this Californio. He escaped in a hail of bullets and managed to survive two more weeks, until cornered in the dense brush not far from the home where he had been brought up, a structure now known as the “Wilson Adobe” near Turri Lane in Los Osos. After a furious, two-day shootout where he and his two companions were surrounded by the Vigilantes, Linares was shot in the head; Walter Murray later noted that he refused the last rites, surely the mark of a “devilish man.” His two fellow fugitives, Desiderio Gonsalves and Miguel Blanco, were captured alive, thrown into jail (Site #3), put on “trial” by the Vigilantes, and hanged (Site #2).